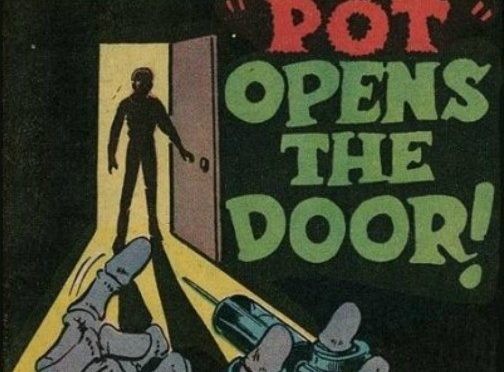

Marijuana has held a reputation as a “gateway drug” for decades. A gateway drug is one that is so addictive that people who use it need to continue to chase a high, and the initial drug soon becomes inadequate. To achieve the high he or she wants, the user moves on to harder drugs in order to achieve the same effect. Much of the evidence which has been used to paint cannabis in this light confuses precedence with causality.

Marijuana as Gateway Drug: Precedence vs. Causality

Precedence simply means that one thing precedes another. In this case, it is not uncommon for marijuana to precede the use of harder drugs. However, if one uses that same logic then drinking water or the act of breathing oxygen are hardcore gateway drugs, because every use of hard drugs has been preceded by the user drinking water and breathing in the 24 hours prior to use. This is, of course, illogical. What is actually necessary to demonstrate that marijuana is a gateway drug is to prove causality – evidence that shows that smoking cannabis leads to harder drug use, not just precedes it.

Before proceeding further, it is important to define the term “drug.” According to the American Heritage dictionary, a drug is “a chemical substance, such as a narcotic or hallucinogen, that affects the central nervous system, causing changes in behavior and often addiction.” Drugs that are not only legal, but very common, include sugar, coffee, tobacco, and alcohol, even though the average American doesn’t think of these substances as “drugs.” What is interesting about this is that these legal drugs are among the most highly addictive. In fact, sugar is eight times more addictive than cocaine, according to widely-published medical research cited by Dr. Mark Hyman.

A team of researchers from Texas A&M and the University of Florida examined data from 2,800 12th-graders in the United States who had participated in a federal study on teen drug use. One of the questions the researchers wanted to answer was which drug teens used first. They found that “the vast majority of respondents reported using alcohol prior to either tobacco or marijuana initiation.” What is even more interesting is that of these three substances, teens were least likely to start using marijuana before using the others.

The researchers wrote that “alcohol was the most widely used substance among respondents, initiated earliest, and also the first substance most commonly used in the progression of substance use.” The research also indicated that the substance was less important than the behavior: “Overall, early onset substance initiation, whether that is alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs, exerts a powerful influence over future health risk behaviors.” For example, teens who had their first drink in the 6th or 7th grade went on to try an average of two illicit substances later; in contrast, teens who waited until the 12th grade to have their first drink tried an average of 0.4 substances – an 80% decrease.

Federal Classification of Marijuana

The Drug Enforcement Agency classifies drugs, substances, and certain chemicals used to make drugs into five distinct categories, or “schedules,” based upon two factors:

- The drug’s acceptable medical use within the United States, and

- The drug’s abuse or dependency potential.

Schedule I drugs (the highest level of classification) include heroin, LSD, marijuana, ecstasy, methaqualone (commonly known as “Quaaludes”), and peyote. The primary reason why these drugs are included on this list is not the drugs’ abuse or dependency potential, but the absence of legally acceptable medical use. This is why heroin is included on the Schedule I drug list but cocaine (which has an extensive list of medical uses) is a Schedule II drug.

Comparing Marijuana to Other Drugs

When contrasted to these legal drugs, it is obvious that marijuana is not highly addictive. Consider this chart which compares the relative addictiveness of multiple drugs:

Marijuana is much less addictive than caffeine (think about a co-worker who can’t live without coffee or Diet Coke), half as addictive as alcohol, and not even in the same ballpark as tobacco.

The chart above demonstrates addictiveness objectively, but what about when one compares the number of people who have actually tried a certain substance? What percentage of those real-world people become addicted? The graph below outlines those statistics:

This shows that the following rates of addiction occur with the various drugs, listed in descending order of proven addictiveness:

- Tobacco: 31.6%

- Heroin: 25.0%

- Cocaine: 16.9%

- Alcohol: 15.0%

- Anti-Anxiety Drugs: 9.2%

- Marijuana: 8.9%

Ironically, neither tobacco nor alcohol even appear on the DEA’s schedule of drugs. Let’s return to the DEA’s reasoning behind its scheduling of drugs and substances: obviously, marijuana is not listed as a Schedule I drug because of its abuse or dependency potential. Instead, it probably appears on this list because of its lack of approved medical applications in the United States.

The lack of medical application for marijuana is based primarily on the fact that cannabis is illegal. This presents an interesting circular reasoning: marijuana is classified as a Schedule I drug (and is therefore illegal) because it doesn’t have many medical applications, and the reason it doesn’t have many medical applications is because it is illegal. This creates a self-reinforcing situation where marijuana can be easily dismissed, not because it is “bad,” but rather based almost exclusively on the fact that it has been declared illegal.

In April of 2015 a federal judge upheld marijuana’s classification as a Schedule I drug because “as long as there remains any dispute among experts as to cannabis’ safety and efficacy,” it should continue to be classified this way by the DEA. As long as this classification remains, however, there is little reason for pharmaceutical companies to invest millions of dollars in research into the medical effectiveness of marijuana – which is what is necessary to change the DEA’s classification of cannabis.

Future for Marijuana

Modern researchers have concluded that marijuana has a wide range of potential medical applications across a variety of conditions.

These potential medical applications can only truly be explored when there is some level of profit motive for pharmaceutical companies to pursue. The first step of this process is to classify marijuana accurately according to its potential for abuse, which is very low.

Please don’t take anything you read here as medical or legal advice. If you need medical or legal advice, consult a doctor or lawyer. The articles and content that appear on this website have been written by different people and do not necessarily reflect the views of our organization.